In last week’s Library Stat of the Week (#19), we looked at the connection between literacy skills among adults and numbers of public and community libraries and librarians, finding a correlation between numbers of librarians per 100 000 people and numbers of adults with low skills. In general, more librarians tend to mean fewer adults with low skills.

The reason for looking at these numbers is the fact that public libraries in particular traditionally have a role in facilitating literacy and learning in their communities.

This often happens in a very informal way, for example simply through independent reading or other use of library resources. However, libraries also have a role as a venue for – or portal to – more formal opportunities.

As underlined in the chapter of the 2019 Development and Access to Information report on SDG4, libraries can indeed be a vital part of countries’ infrastructure for lifelong learning.

So this week, we’ll look at the relationship between numbers of public and community libraries and the numbers of adults (aged 25-64) currently engaged in learning. Once again, we’ll use data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competences (PIAAC). Library data comes from IFLA’s Library Map of the World.

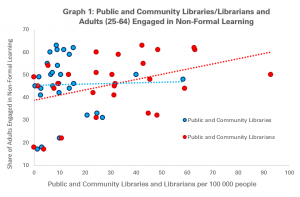

The first graph looks at the relationship between the number of public and community libraries and librarians per 100 000 people and the share of the adult population in non-formal education (source). Each dot represents a country for which data is available for adult learning, and for numbers either of public and community libraries and librarians.

In a similar result to that found in last week’s Library Stat of the Week, there is correlation in the case of public and community librarians, with more librarians tending to mean more people engaged in non-formal learning. The link is less strong in the case of public and community libraries.

As with last week, this could be explained by the fact that it is the presence and support of library and information workers that helps people to make connections with learning opportunities.

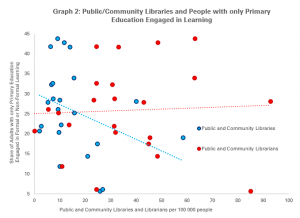

The next question is to see whether there is any sign of a connection between numbers of public and community libraries and librarians, and the number of people with lower levels of education (who have not completed secondary education) involved in adult education.

Graph 2 does this, using figures for adults involved in all sorts of learning (formal, non-formal and a combination of the two) (source). This provides a less positive picture, with no obvious relationship between access to learning and numbers of librarians, and even a negative one with numbers of public libraries.

This suggests that governments are not yet making full use of libraries in order to help those who have not had the opportunity to reach the end of secondary education to access education. Given the evidence of what libraries can do, this is a chance missed.

Nonetheless, it is also worth bearing in mind that some countries have lower levels of adult education in learning than others in general, which helps put the number of those with only primary education in context. Other drivers of access to lifelong learning can of course be factors such as how this is paid for, or the volume and attractiveness of the offer.

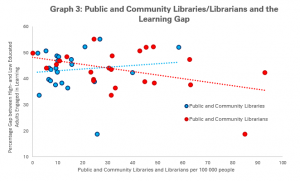

We can get an alternative perspective here by looking at the ‘learning gap’ – the difference between the share of adults with university and only primary education who are currently engaged in non-formal and/or formal education (source).

This in interesting as an indicator of equality, as a smaller gap means that there is a lower risk of people starting with less education falling further behind. Graph 3 shows what happens when we compare the size of this gap with numbers of public and community libraries and librarians.

Encouragingly, we see a return to the sorts of figures seen in Graph 1 and last week’s Library Stat of the Week, with larger numbers of public and community librarians per 100 000 people correlating with smaller gaps in access to learning.

While, as ever, correlation does not mean causality, one explanation here would be the role that libraries can play in ensuring that adults can have a second chance. While those who have been to university may feel more confident in looking for opportunities for opportunities for further learning, or be in jobs that welcome and support this, this may be less likely for those with only primary education. Libraries can help fill the gap.

With many – especially those in lower-skilled, lower-paid jobs – facing unemployment in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments would do well to invest both in skills provision, and the libraries that help those who need it most to find it.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.