Author: Yeo Pin Pin, Head of Research Services, Singapore Management University Libraries

Academic libraries in Singapore support Open Access and Open Science trends in the world. Some of the trends can be seen in the ACRL Scholarly Communication Toolkit. Let me outline how we have supported these trends in Singapore.

Open access repositories

Starting from 2005 with the first institutional repository (IR) by the National Institute of Education (NIE), the academic libraries in Singapore progressively launched their own IRs: Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in 2009, National University of Singapore (NUS) and Singapore Management University (SMU) in 2010. The latest IR was launched by the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) in 2021.

The platforms used for the IRs are either open source on DSpace or commercial platforms like Digital Commons and Figshare. NIE, NUS and NTU use DSpace and engage a vendor to help them manage the technical side. SMU uses the hosted solution by Digital Commons and SIT uses Figshare. The library staff of the IRs in Singapore focus on supporting institutional policies, integration with internal systems, building content and promoting usage and engagement within the community.

Content in repositories

The IRs in Singapore showcase the research done at their institutions by having records, and the full text where possible, of publications by their researchers and faculty members. The IRs in Singapore also include theses and dissertations. The IRs in Singapore have good discoverability and downloads.

Some of the unique content available in NUS Digital Gems include the papers of Edwin Thumboo, Koh Kim Yam and the Earl of Cranbrook. The NIE IR has the manuscripts of Dr Muhammad Ariff Ahmad. The SMU IR has the oral history interviews and transcripts with the pioneers who set up SMU and the leaders who helmed SMU subsequently.

Historical newspapers from Southeast Asia published in Chinese, Jawi and English were digitised and made available open access in NUS Digital Gems. Recordings of musical performances from the NUS Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music are another unique offering in the NUS IR.

Growth in open access publications

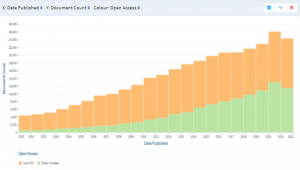

Using the data in Lens.org, the growth in the number of open access publications in Singapore has been steady and has grown to 50% in 2021 from 11% in 2000.

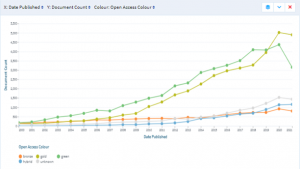

Let us look at the breakdown by type of open access in Singapore using the data in Lens.org. Singapore started with more green open access publications than gold open access from 2000 to 2019. From 2020, the number of gold open access publications exceeded green open access. Bronze open access publications was 7% in 2021 with hybrid at 10%. We have not seen bronze open access increasing in proportion in Singapore, as found by Piwowar, et al (2018).

The above charts show the growth in percentage of open access publications over the past 20 years. The type of open access has also shifted, from mainly green with less gold open access to more gold and less green open access. From 2019, there were more gold open access publications than green open access publications in Singapore. This was possibly aided by funders allowing grant funding to be used for article processing charges and more awareness of the benefits of open access.

Open Data and Open Science

NTU was the first institution to have a research data policy which was effective in 2016. NIE also had their Data Management Plan and Research Data Management Policy in place by 2017 and revised by 2021. SMU crafted its research data policy in consultation with the library, the schools and the faculty and the policy was in effect from January 2020. SIT put in place their research data policy in 2021. The libraries in Singapore had worked with their respective research offices and key stakeholders to put in place the infrastructure to support the policies. The other institutions are working on their policies.

NTU Library has an Open Science & Research Services team to focus their efforts on creating awareness and advocating the best practices in open science among the NTU community. At SMU, we have a Data Services team to focus our efforts on providing services for accessing, managing and working with data for our community. The libraries in Singapore organise and conduct learning sessions about relevant topics on open science for their own community. Together we are also working to raise awareness about open science in Singapore through organizing events that are open to the academic community. Some examples were the webinar on Institutional repositories and sensitive data in 2020, and COAR Asia OA Meeting in 2021 organised by the Singapore Alliance of University Libraries’ Research Support Task Force.

Data repositories

NTU launched its data repository (DR) on the Dataverse platform in 2017, followed by NIE in 2018 using the same platform. In 2018, NUS enhanced its existing repository on the DSpace platform to take in datasets. In 2020, SMU launched its DR using the Figshare platform. In 2021, SIT launched its integrated repository for both papers and data using the Figshare platform.

There is recognition that not all data can be made open. Hence, NUS, NIE and NTU set up systems to store the data that was still in-progress or sensitive.

Research funders

The Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) put in place an open access mandate in 2013 and set up an IR to support their researchers to comply with the mandate. In 2016, the major research funders in Singapore introduced a common clause that required that the publications arising from their funded research be made open access within 12 months of the official date of publication in a suitable repository. The funders then allowed the use of the grants for Article Processing Charges. These changes provided incentives to researchers to make their publications open access and even gold open access.

Publisher agreements

NUS Libraries had negotiated deals with several publishers for discounts on the Article Processing Charges (APCs) for NUS authors. The Singapore Alliance of University Libraries (SAUL) has a committee working on negotiating with selected publishers for better terms and conditions for the group and exploring whether transformative deals would work in the Singapore context.

Conclusion

In Singapore, we follow the trends closely and then work within our own institution to implement those that suit the needs of our institutions. We also collaborate and learn from each other about best practices. Open access is on a strong footing now after steady growth over a decade. We are trying out some deals with publishers to make publishing open access and gold open access easier for our researchers. We are supporting and promoting Open Data and Open Science and this area is still new for us, but we hope to make further progress in this area.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2022). Scholarly Communication Toolkit. Available at: https://acrl.libguides.com/scholcomm/toolkit

Conrad, Lettie. (2022, January). 5 scholarly publishing trends to watch in 2022. Available at: https://blog.scholasticahq.com/post/scholarly-publishing-trends-2022/

Dempsey, Lorcan. (2022, April). Workflow is the new content. Presented at Digital initiatives Symposium. Available at: https://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/presentations/2022/workflow-is-the-new-content.pdf

Hayashi, Kazuhiro. (2021). How could COVID-19 change scholarly communication to a new normal in the Open Science paradigm. Patterns, 2 (1), 100191. DOI: 10.1016/j.patter.2020.100191

Ooi, Lian Ping. 2021. Open access and open science in Singapore. Presented at COAR Asia OA Meeting. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/asiaoa2021/program/agenda/6/

Piwowar, Heather, et al. (2018). The state of OA: a large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles. PeerJ, 6, e4375. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.4375

Links for repositories in Singapore

- A*STAR A*OAR http://oar.a-star.edu.sg

- DR-NTU (Publications) [DSpace-CRIS] https://dr.ntu.edu.sg

- DR-NTU (Data) [Dataverse] https://researchdata.ntu.edu.sg

- NIE Digital Repository [DSpace-CRIS] https://repository.nie.edu.sg

- NIE Data Repository [Dataverse] https://researchdata.nie.edu.sg

- NUS Scholarbank [DSpace-CRIS] https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg

- NUS Digital GEMShttps://digitalgems.nus.edu.sg

- SIT Institutional Research Repository (IRR) [Figshare] https://irr.singaporetech.edu.sg

- SMU InK [Digital Commons] https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/

- SMU Research Data Repository [Figshare] https://researchdata.smu.edu.sg